In April’s cover story, Tony Slinn explored development of the first vessel based on a wind-powered carrier concept, due to take to the seas by 2025

The Oceanbird concept will be the world’s first full-size wind-powered pure car and truck carrier (PCTC), and aims to slash emissions by at least 90% compared with today’s diesel carriers. In February 2021, Wallenius Wilhelmsen announced the company intends to place an order for the first vessel – Orcelle Wind – which should be sailing by 2025.

That order is a milestone in the ongoing wPCC (wind-powered car carrier) project – a three-year (2019-2022) R&D venture carried out by a Swedish consortium led by Wallenius Marine and involving the KTH Royal Institute of Technology, along with maritime research consultancy SSPA. It has a US$8.7m budget, of which US$3.8m is financed by the Swedish Transport Administration.

Project coordinator Wallenius Marine owns the concept and is contributing design and logistics expertise. The firm, along with sister company Wallenius Lines, owns part of global ro-ro shipping and vehicle logistics company Wallenius Wilhelmsen, to which it provides both ships and ship management. KTH’s role concerns aerodynamics, sailing mechanics and performance analysis, while SSPA’s contribution includes development and validation of new testing methods, hydrodynamic and risk simulation, and also aerodynamics.

Sailing back to the future

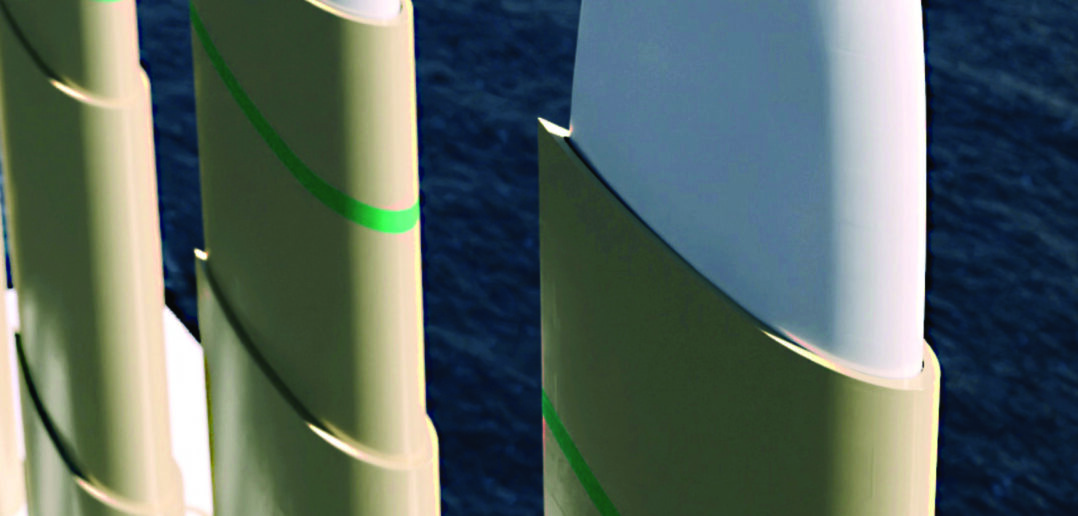

In September 2020, following tests with a 7m model, the consortium unveiled the Oceanbird concept design. At 200m long and 40m wide, she will be the largest sailing vessel ever built, with 80m-tall sails giving her a height above the water line of 105m. Those sails, which resemble aircraft wings, are likely to be built from aluminum, steel and composite materials and will be capable of ‘reefing’, i.e. retracting. The vessel will take about 12 days to make an Atlantic crossing (compared with eight days by a conventionally powered PCTC), and will also have a backup engine to ensure timely arrival for port slots, as well as for maneuverability.

“Regarding the engine, we’re looking at several fuel options, including LNG and biofuels, and synthetics such as LBG, hydrogen and ammonia. We’ll choose the most environmentally friendly option,” explains naval architect Carl Fagergren, Wallenius Marine’s ship design and new-building project manager. “We’ve yet to pick a specific engine manufacturer, though we are talking with established suppliers.”

In light of the International Maritime Organization’s 2050 target to cut climate-changing emissions from shipping by half (from 2008 levels), Fagergren adds, “At the moment, we state that the vessel will cut emissions by 90%, but our goal is zero emissions. Our vision is to lead the way toward truly sustainable shipping, and by that we mean that shipping should not leave a negative mark on the environment, nor on humans, but it should provide a reasonable economic return.”

Though the first vessel is on order, Fagergren notes that, “The experiments with the 7m model have confirmed that our design works as intended. But many more thorough tests are coming, and we may discover things that require a design change.”

“We carried out the model sea trials outside Stockholm, in an inlet from the Baltic Sea, and we also tested indoors with a further 7m model in a tow tank in Gothenburg,” adds Oceanbird commercialization vice president Richard Jeppsson. “We also have plans to mount and test a full-size wing sail on land, but when and where has not yet been decided.”

“The consortium partnership is absolutely key,” explains Wallenius Marine naval architect Carl-Johan Söder. “Between SSPA’s knowledge of model testing and advanced fluid dynamics calculations, KTH’s expertise in problem solving, and our design and logistical experience, I think we’re onto a winner.”

The design will be finalized by Wallenius Marine and classified by DNV, and is on schedule to be ready this year, or by early 2022, Jeppsson confirms. “The vessel will need something like 18 crew members, depending on regulations for safe manning, which we will investigate in the future. Selection of a shipyard to build it will be a procurement process in line with regular new-builds – no pre-qualification or preliminary choices have been made.

“We’re currently investigating other types of vessel that will be suitable for this wind power technology, and trying to interest shipping companies to place an order too,” Jeppsson continues. “We can’t specify anything yet, but stay tuned!”

Supplier demand

The sail provider has not been confirmed and, as Fagergren notes, that process could involve more than one supplier.

“I can say that there will be one wing control system [WCS] per wing and one vessel control system [VCS]. The systems are not integrated, but work together: the five WCS send information to the VCS about each wing status and position, as well as information from various sensors; for example, temperature, wind speed, wind direction, propulsion force and heeling moment. The VCS uses that information to calculate the optimal course and speed, as well as the setting on the wings, propulsion machinery, rudder and more.”

“At 80m tall, the sails are a first and there are likely to be different pressures at different points on them, contributing to the load distribution,” says Mikael Razola, Wallenius Marine’s Oceanbird sailtech project manager. “One is the ground boundary layer, where typically the wind speed increases with height. This effect is, however, rather small due to the height of the wings above the water surface. Another effect is due to the hull presence, which influences inflow. We’re working with different technical systems to cope with the inflow characteristics.”

The hull has been designed for a large sailing cargo vessel, with further developments stemming from that, including speed, steering technology, hull shape and appearance, and design and construction of the rigging.

“It’s a mix of aerodynamic and shipbuilding technology,” Razola says. “Full use of wind power’s potential depends on understanding the mutual interaction between the hull and sails, from the large-scale flow situation to the detailed interaction effect between the hull and wing sail. This is something that has been carefully considered in the design.

“As for safety systems,” Razola continues, “there are several interacting, in order to make the vessel and wing system safe to operate under all conditions. These range from system and hardware redundancies, to sail reefing strategies and technology, the use of weather routing, real-time monitoring systems, and more.”

Next up for the concept, confirms Wallenius Wilhelmsen CEO Craig Jasienski, is application of the company’s extensive ro-ro knowledge to the detailed design of the vessel’s features, and a comprehensive viability evaluation.

“Orcelle Wind is an important step on the journey toward zero emissions, but will also need to prove its commercial viability,” he says. “We have had positive signals from customers such as BMW, Volvo and Mercedes-Benz. Success here will be heavily dependent on partnerships with customers and whether there is market commitment to adopting radical, innovative measures to drastically reduce the environmental footprint of outbound supply chains.”