Having received approval in principle from Lloyd’s Register, Feadship is accelerating development of an agnostic fuel system as the foundation of its new generation of carbon-neutral superyachts, due in 2030.

Decarbonization is a growing priority across the maritime sector, but the pathway to that destination is still unclear. The influx of non-fossil fuels and the likelihood of variability in their near-future supply means adaptability is a vital feature for new vessels, and this is having a major influence on ship design. For shipbuilder Feadship, developing and certifying a flexible fuel system is a linchpin of its first zero-carbon superyachts, and it’s a process increasingly driven by customer demand.

“It’s changing quite rapidly,” explains the company’s head of R&D, Giedo Loeff. “Our clients are becoming increasingly aware of their [boats’] environmental impact and they are concerned. There are no regulations forcing them, but there is a lot of societal push and voluntary behavior, because they know we have to change our way of dealing with energy.”

A marine architect by background, Loeff joined Feadship (the First Export Association of Dutch Shipbuilders) in 2015, having previously managed projects for member yards Royal Van Lent and De Voogt, as well as the Maritime Research Institute Netherlands (MARIN).

He heads a department with a broad remit, including not only fuel and power systems but also materials, structures and digitalization across both of Feadship’s parent companies. Sustainability is an increasingly influential topic, spanning each of those elements and requiring new design methods and tools, as well as retraining of staff.

He heads a department with a broad remit, including not only fuel and power systems but also materials, structures and digitalization across both of Feadship’s parent companies. Sustainability is an increasingly influential topic, spanning each of those elements and requiring new design methods and tools, as well as retraining of staff.

Prepping for the future

The route to 2030 is happening in stages and some of the building blocks are already in place. The 83.5m Savannah, delivered in 2015, combined a streamlined hull with the company’s first diesel-electric propulsion system to achieve a 30% reduction in fuel consumption. It also introduced a DC bus, developed with Schneider Electric and linked to the propulsion and main power systems, which set the standard for subsequent builds. New-generation Feadships will begin delivery this year, employing a DC bus with variable-speed gensets, a battery and electric propulsion without shaft lines.

“In making the step toward electric main propulsion, having high-power components based on the DC bus is important,” says Loeff. “Internal combustion engines running on alternate fuels and fuel cells have a lower load response. To improve the efficiency of those systems you want to mitigate and balance the load on the fuel cells and on dual-fuel or spark-ignited methanol engines. That step toward electrification is very sensible, because it is easier to configure with batteries or fuel cells.

“We are building yachts with up to 10MWh of batteries, because our clients like to switch off all internal combustion engines every now and then for silent operation,” he continues. “When we start to use fuel cells on alcohol fuels, then those big battery banks will not be required. You can operate very quietly on methanol and you don’t have a [range limitation], because you can carry an adequate amount of methanol on board. Fuel cells will take over from a battery bank, so maybe it can be replaced by a smaller, higher-density, new-generation battery with a fuel cell. Forward compatibility is crucial.”

The first multifuel vessels will set a similar standard. Feadship states that 90% of a yacht’s carbon impact is in fossil fuel supply and consumption, and recent new-builds and refits have included single- or dual-fuel engines compatible with hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO). It is open-minded about future options. The company is a co-founder of the Green Maritime Methanol project, a consortium of 30 partners that assess the fuels’ feasibility for the sector, and vessels will be designed with compatibility for an as yet unknown mix of paraffinic and alcohol fuels as the production is scaled up.

“With what’s known as a hard changeover – say, going from diesel to methanol – our clients could have a problem because they will always need to source methanol,” Loeff continues. “So you want to have flexibility in the energy transition. There may be new production methods for other fuel types. For example, if you produce ethanol from methanol you can sail much further, so our clients may want to choose that fuel.”

Covering all bases

Covering all bases

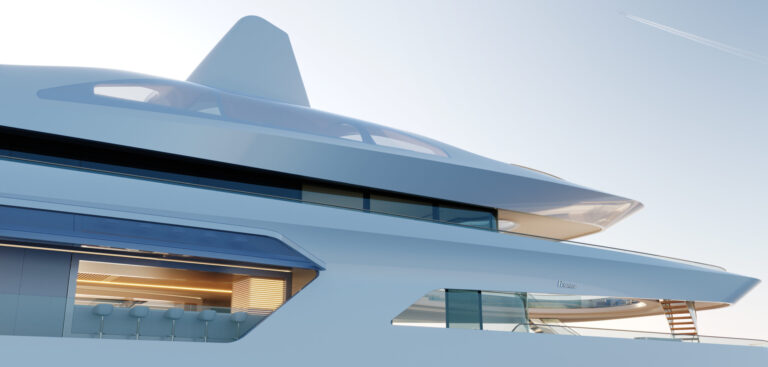

Solving those challenges was a key theme for the 82m Pure design concept, shown at the Monaco Yacht Show in 2021. It demonstrated how future vessels could benefit from a redesigned tank deck, configured with three powertrain options in mind. The 2024 version combines downsized diesel engines with a mains-rechargeable battery, providing an electric range of 120 nautical miles. Its oversized fuel tanks provide headroom to switch to methanol generators in 2027 without compromising on range, before switching to fuel cells in 2030.

In the meantime, Feadship is working with suppliers outside the usual marine supply chain to develop solid-oxide fuel cells as a more efficient alternative to today’s PEM units. Loeff believes this could offer quiet cruising with a low environmental impact, and use of a smaller battery pack would offset switching from combustion engines to larger fuel cells. This is also projected to match the 5,000 nautical mile range of the company’s current vessels.

Most of the required modularity for that transition is already commonplace. Power systems are mounted on skids and fuel-handling areas can be refitted as vessels transition to new technology. However, the fuel storage and pipework that take it from the bulker port to the engine room is a fixed, structural element of the vessel that can’t be replaced and also falls within Feadship’s own remit. With no clear winner yet, the next stage of development is a standardized storage system certified for today’s fuels and whatever comes next. It’s a challenge that Loeff says can be simplified by focusing on the worst-case scenario.

“You need to have safety barriers and safety systems that are adequate and acceptable for the least-safe fuels,” he continues. “Methanol, for instance, has a very low flashpoint and is highly toxic. We are also looking at ethanol, HVO and diesel, and there are also fuels we don’t really see yet that are viable – solid ethers such as methyl ether – and may be interesting. If we could design and build a system that can also be used with those fuels without a lot of additional work, we will. Then the system will be as flexible as possible.”

“Flexibility is key in our design. The things you need to determine are: How do you build a tank? Where are the double barriers? How do you create a tank entry? What is the connection of sensors to these tanks? Those things we will standardize. The fuel pipes should be compliant with these various fuels and they also need to be certified.”

Despite the near-term diversity, Loeff believes that yachts have some specific requirements for future fuels that are better served by liquids than gases, as they suit the structural storage and are more space-efficient for long-range vessels. Feadship is currently building its first hydrogen hybrid, using a fuel cell system, but expects only limited applications due to its low power density. In the near future hydrogen could supply auxiliary power and enable low-speed sailing, but only for larger vessels.

“There will still be other innovations to work with,” Loeff continues. “For instance, organic Rankine cycle waste heat-to-electric systems can be very interesting. Currently they are still quite low on power density and you get only a couple of percent better efficiency. The HVAC unit [is an example of somewhere] we could still make a couple of steps forward. These are the sorts of things we are working on, and the momentum to do so is growing all the time.”

“We see that more and more clients want to invest in fuel cells – they want to adopt these alternative fuels,” Loeff says. “We don’t have to explain to them that the energy sector is making those steps, as they are already aware. You only need a couple of clients pushing you in the right direction to take the necessary steps. The others will get a new generation of Feadships because it’s the new normal, the new standard.

Design freedom

Design freedom

Emerging technologies offer exciting new design possibilities for future vessels. One of the noteworthy features of Feadship’s Pure concept was a concealed command center, using cameras and other sensors and the company’s Foresight program to help crew find the most efficient, comfortable route while also freeing up a forward-facing view for clients. Loeff notes that new propulsion systems and tank designs also offer more design flexibility by decoupling the engine and propulsion unit.

“We have smaller, lower engines, so we can design single-tier engine rooms. This means we only need a tank deck – which is a technical deck with all the stuff that relates to the power system – lower deck and engine room. Then we can have a lower deck with full accommodation – you want that for yachts, because it’s the part that you actually use.

“Having a DC bus with variable-speed gensets means you can tune your work points for high efficiency and low emissions, but also for comfort because all engines have a certain vibration and noise profile that is inherent to the design. If you know that design, you can also optimize the working points for less excitation and noise. The RPM of a traditional genset is pretty much fixed. It’s chosen wisely, but is much less variable.”

Learning from big data

All new Feadships are equipped with a hardware-agnostic remote monitoring system called Polestar, which enables the company to detect and troubleshoot faults and offer predictive maintenance. Loeff says this will expand the amount of data that can be downloaded from vessels, enabling machine learning to play a bigger role in R&D.

“We already gather big data like AIS in combination with MetOcean data to find the very high-level operational profiles and load profiles for our designs. If you match these data sources you see which seagoing conditions the yachts are actually used in, so that’s what we need to design them for,” he explains.

“For instance, we have one very important system on board – the HVAC system. We design that [for each operation] and we can deduce the load cases from these data sets – how often are they used and whether they are exposed to certain climates.”